Not in the mood for reading?

You can listen comfortably to all the information here and while exploring the region.

The interdependence of research, university and colonial politics

Sience, research and education are still viewed in a positive light in current language. To discover something is an enrichment for human knowledge over the world.

“Wissenschaft schafft und konturiert Wissen, und alles rassistische Wissen, das uns bis heute begleitet, hat eine Absicherung in und durch Wissenschaft und ihre Institutionen erfahren.”

Arndt 2017, S.65.

“Science creates and constructs knowledge and all racist knowledge, which has accompanied us until today, has experienced a protection in and by science and its institutions”

Arndt 2017, p.65

But this knowledge is never detached from the dominant world views and ideologies of the respective society. Following the discovery of the continent of America it came to an extinction of indigenous populations by millionfold deportations and enslavement of human beings coming from the African continent. Knowledge is not only impartial and neutral. It can lead to violence or can be violent itself as shown by the human catigorization in the 19th century. Susan Arndt says that at the end of the 19th century “each relevant descision and development was adjusted as ‘scientifically proven'” (Arndt 2017, p. 64). It is not possible to conduct research detached from the geopolitical and social relations, in which we operate. In times of the colonialism, science more or less well-founded, had a central role for the legitimation of its own proceeding research. The origin of many disciplines like geography, ethnology, tropical medicine or biology can be lead back to the colonial interests of Europe and Germany.

Colonial expeditions

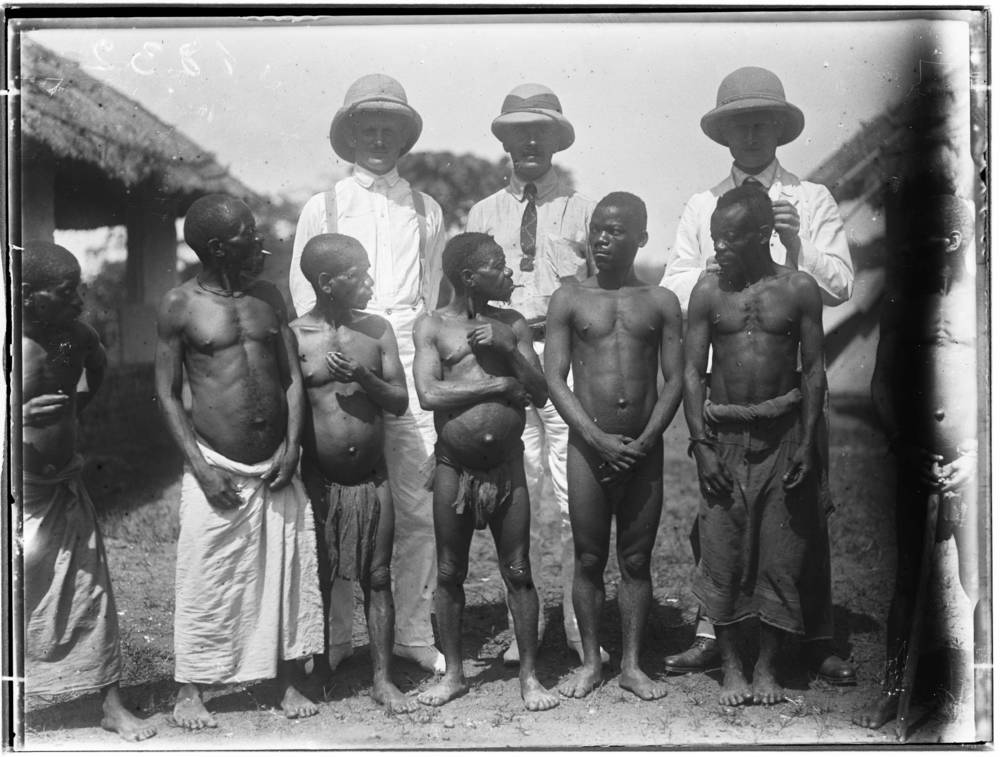

Expeditions into countries of the south played a special role. The aim of the expeditions were very often to redeem “white spots” on existing maps like in Africa. It was performed with a particular eagerness to be the first European or the first German in a determinded region, to name plants, animals, volcanoes, and other things with names of white, male explorers without considering the knowledge of the natives. In an attitude of white supremacy the fundamental beliefs persisted, that they render a service to humanity by classifying and surveying all the plant and animal life, and even human beings, using specific criteria which were developed in Europe. While everything could be made into a certain object, the Europeans considered themselves as the acting and knowing subject. A desire for adventures and hunting was a profound motivation of the so-called researchers. Therefore it must be reconsidered if the expeditions and their results can be classified as science.

Hermann von Wissmann

The Rostock lieutenant Hermann von Wissmann was famous for crossing Africa from east to west as the first european. In 1883 he was convinced that “he did a further step for the illumination of the continent Africa which was defending itself so tenaciously against culture” (Wissmann zit. nach Pade 2001, p. 202). Wissmann is still honored on street names in some cities as “Afrikaforscher” (‘Explorer of Africa’), subsequently he was known and celebrated for his “successful”, brutal and military actions during the supression of rebels of the coastal population against the German colonial government in German East-Africa, which is today The United Republic of Tanzania. He performed massacres in local towns, plundered and burnt them down. In retrospect it was his expeditions from East Africa to West Africa which paved the way into the Belgian and later the German colonial policy.

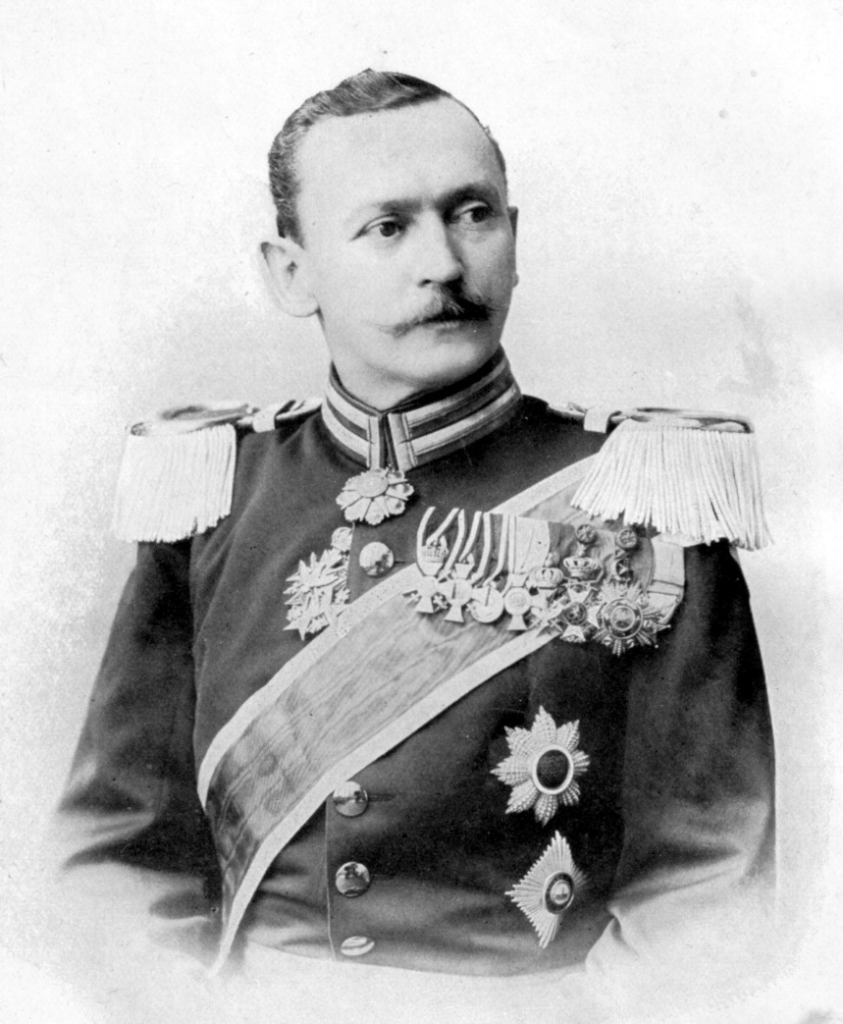

Herzog Adolf Friedrich

Adolf Friedrich, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (1873 – 1969) was known for numerous expeditions to Africa and made his mark as “Afrikaforscher”. Later in life he operated as a colonial politician. Overall the house of Mecklenburg attracted attention due to an engagement in colonial policy in the German Empire. The House of Mecklenburg had strong connections to the House of Hohenzollern and thereby to the German emperor Wilhelm II. Until the death of his first wife, Friedrich resided in the Palaisgebäude (‘palais’) at the Universitätsplatz.

His interests for distant countries began with a journey into the Middle East, which he received as a gift for passing the German secondary school. In 1907/08 he undertook his first so called ‘scientific expedition’ from East Africa to West Africa, which was subsidized by the German Colonial Society. His second expedition took place in 1910/11 in West Africa, Chad. He brought numerous collections along from his expeditions to Germany, which included many skulls and bones. Most of the objects went to the Berlin Museum for Botany, Zoology and Ethnology. Some he devised to the Ethnographic Museum in Rostock. While the scientific evaluation was left to Jan Czekanowski, an ethnologist from Berlin who published a 8-volume editon referring to the pieces, Friedrich published his diary entries “Ins Innere von Afrika” (“Into the innermost of Africa”). This was a report on the German scientific Central-Africa-Expedition in 1907/08 which should arouse interest among young people for Africa and the colonial policy of the German Empire. He indulged in memories of hunting and slaying animals like elephants and he tried to impress readers by using descriptions of cannibals who were eating white people.

In 1912 the enthusiast of Africa acquired a position as a governor in Togo for two years. Pade, a scientist of Latin America in Rostock expresses that Friedrichs time as governor did not differe from others. He approved of the land taking from the native population by plantation owners and used violence if the natives tried to take it back from them. Indeed he didn’t enforce an unlimited rise of taxes. But he decreeded an order that the children of German men and black women shall not be named after the father. It is not unlikely that this happened in accordance to his own interests. The topic of sexual contacts with native women and the abuse of minors is handed down and was critically seen by the native chiefs.

After the relinquishing of the German colonies due to the Treaty of Versailles after the defeat of Germany in the First World War, Friedrich was still appointed vice president of the Germany Colonial Society to recover the German colonies. In the 1930s he was working for the Werberat der Deutschen Wirtschaft (German advertising standards authority), which was subdivided under the propaganda ministry of Goebbels. He was working in South America. Friedrich was a figurehead of nostalgia for the colonial policy in the old Federal Republic of Germany until the 1960s (Pade, Buchka, p. 34). Aside from his engagement in the German and the International Olympic Comitee, he was highly decorated for his colonial-scientific and colonial-political service. He got two honory doctorates from the University of Rostock.

Corresponding to scientific principles his publications should be critically reconsidered, likewise to the ones of Paul Pogge, whom we spoke of earlier.

Culture of memory and honory doctorates

In 1912 Friedrich got an honory doctorate from the philosophical faculty of the University of Rostock. On the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the University of Rostock, he received another honory doctorate from the medical faculty. At the same event Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck was honored with a honory doctorate for his glorious actions during the First World War. As commander of the protection force for German East Africa (today: Tanzania (without Zanzibar); Rwanda; Burundi; Kionga-Triangle in Mozambique), he was the only general who withstood during the war under the the loss of many lives of black humans and mercenaries, so called askaris (This expression was used for native soldiers in the colonial forces of the European powers). In preparation of the festivities of the 600th anniversary of the university, there is a chance to confront it critically with the choices which were made in the course of colonialism and nationalism in 1919, and to voice the quenstion, if they are still ethically acceptable. In 2016, the city of Freiburg demonstraded that how and street names appear is not carved in stone. They questioned them critically and added or changed things after a commitee looked closer into the personalities they were named after. A similar procedure could be used for the honory doctorates of universities of Rostock. We are looking forward to an examination of these topics in the course of the university’s anniversary and are willing to participate in the process.

Culture of memory and historiography

What do you think about this quote, regarding the previous information?

„Es ist wahrscheinlich eine der letzten großen Expeditionen [gemeint ist Friedrichs zweite Expedition von 1910-11] gewesen, die diesen Namen verdienten: mit Trägern und Proviantdepots, Trinkwasser, Tauschwaren und … einem Kunstmaler! Es ging durch Busch und Savanne und kam zur Begegnung mit kannibalischen Stämmen.“

Goetze 1987, S.77.

“It was probably one of the last big expeditions (Friedrichs second expedition from 1910 – 1911), which deserved the name: with carriers, a depot of supplies, drinking water, goods for trading and a painter. They went through the bush and the savannah and encountered cannibalistic tribes”

Goetze 1987, p.77.

What can WE do?

What do you think about the proposal to search for alternative sources of historiography which does not only include the European and mostly racist characterisation of the continent of Africa? Unfortunately, it is not so simple to find historical sources from local natives. These were mostly never written down. In postcolonial studies of literature and history, strategies were developed to read European sources against the grain. Behind the voices (and degradations) of colonial officials, merchants and missionaries could the actions of resistance be fragmentarily adumbrated?

Sources and for reading

- Susan Arndt, Rassismus. Die 101 wichtigsten Fragen, München ³2017.

- Martin Buchsteiner/Antje Strahl, Zwischen Monarchie und Moderne. Die 500-Jahrfeier der Universität Rostock 1919 (Rostocker Studien zur Universitätsgeschichte 4), Rostock 2008.

- Kommission empfiehlt Umbenennungen von Freiburger Straßennamen: http://www.freiburg.de/pb/site/Freiburg/node/1017982/Lde/zmdetail_14794301/Linnestrasse.html?zm.sid=zml3zhm6elz1; last accessed 04.12.17.

- Adolf Friedrich, Ins innerste Afrika. Bericht über den Verlauf der deutschen wissenschaftlichen Zentral-Afrika-Expedition 1907-1908, Leipzig 1909.

- Rolf Goetze, Der „Afrika-Herzog“. Ein Erinnerungsblatt an Adolf Friedrich, Herzog zu Mecklenburg, in: Afrikanischer Heimatkalender (1987), 75-79. (attention: discriminating).

- Doris Griesser, Wenn Wissenschaft zu Herrschaft führt, in: Der Standard 25.11.2015: http://derstandard.at/2000026345145/Wenn-Wissenschaft-zu-Herrschaft-fuehrt; last accessed 14.12.17.

- Rudolf Junack, Adolf Friedrich Herzog zu Mecklenburg. Leben und Wirken, Hamburg 1963. (attention: discriminating).

- Thomas Morlang, Der umstrittene „Kolonialheld“ Hermann von Wissmann, in: Ulrich van der Heyden/Joachim Zeller (Hg.), „… Macht und Anteil an der Weltherrschaft“. Berlin und der deutsche Kolonialismus, Münster 2005, 37-43.

- Werner Pade, Gerhard von Buchka. Kolonialpolitik und „Kolonialwissenschaft“, in: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Wilhelm-Pieck-Universität Rostock (1988), 34-40.

- Online collection: https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/1900851; last accessed 3.12.2020.

- Werner Pade, Zwischen Wissenschaft, Abenteuertum und Kolonialpolitik. Adolf Friedrich Herzog zu Mecklenburg, in: Martin Guntau (Hg.), Mecklenburger im Ausland. Historische Skizzen zum Leben und Wirken von Mecklenburgern in ihrer Heimat und in der Ferne, Bremen 2001, 201-212.

- Edwin Sternkiker, Unter den Riesen von Afrika. Herzog Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Schwerin beim Stamme der Watussi (Berühmte Mecklenburger), in: Mecklenburg-Magazin 07.02.1992, 3. (attention: discriminating).

- Autor nicht angegeben, Ein großer Mecklenburger und „Afrikaner“. Herzog Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg schied von uns, in: Unser Mecklenburg. Heimatblatt für Mecklenburg und Vorpommern 332/333 (1969), 3. (attention: discriminating).